27 July 2017

Solo

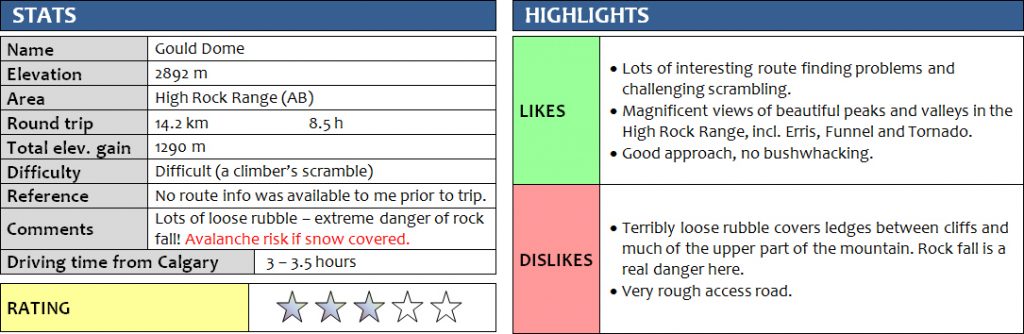

Gould Dome is a distinctive and easily recognizable peak in the High Rock Range with its characteristic “layer-cake” arrangement of alternating cliffs and ledges that entirely surround the mountain. This attractive but also daunting looking mountain first caught my eye when I went up nearby Mount Erris in 2016. Later that year, Richard and I enjoyed a great weekend camping along the rough access road east of Gould Dome, where we managed to scout out a good approach route up its eastern flanks. One year on, an opportunity came up to find out if a scramble route up the east face of Gould Dome exists. Sitting just south of Tornado Mountain, I figured that these two mountains would make for a great 2-day combo with a camp down at the same spot where Richard and I had stayed before.

It takes a bit of patience (and a higher clearance vehicle) to reach this area from Calgary, but it’s well worth it. The Dutch Creek access road is in good shape (recently graded) for the first 30-40 minutes or so, then it quickly degrades into a bumpy dirt track. After about 15 km from the Forestry Trunk Road, I took a right at a T junction and drove for another 2.2 km uphill on a very rough and narrow track that my CR-V barely managed to negotiate. I set up my tent in a nice grassy spot by the road about 800 m from a creek, which my car wouldn’t have been able to cross anyway.

Edit August 2019: The rough access track that branches off to the north from the Dutch Creek Road at the T junction is now closed to motorized traffic, as kindly reported by Geoff Hardy. This means you’ll have to camp/park here and then bike/hike an extra 2 km or so (up to the point where I camped). There are dozens of large berms and ditches along the track now, making a bike approach from this side much more difficult and slower than before.

After setting up camp, I hiked north along the track, rock hopping over the creek, and then headed west on a series of old logging roads, now all reclaimed by nature but affording good travel through the forests. There was no one around of course, no roaring noises of ATV’s or dirt bikes, and I had this peaceful land all to myself.

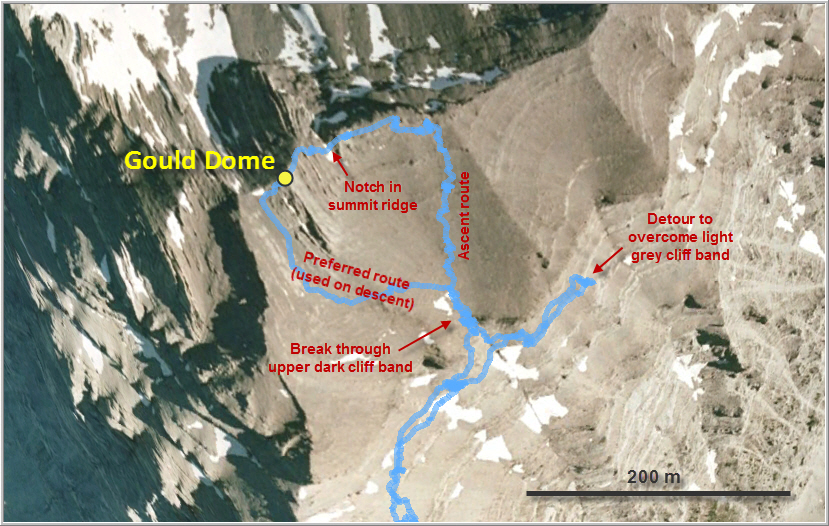

A brief section of mild bushwhacking was necessary to get from the end of one of the logging roads into the access drainage on Gould Dome’s eastern flanks. Thankfully, I had the GPS track from our previous scouting trip with me, which made route finding here a breeze. I then followed the drainage on its left (south) side, just inside the forest, to avoid a jumbled mess of piled up trees in its centre, probably the result of avalanches coming down here in winter and spring. The drainage opened up and steepened once I came above treeline – a good spot to take a rest and analyze the remainder of the route. Above me were a series of intimidating vertical cliff bands alternating with rubbly ledges and sills in between, stretching horizontally across the entire east face of the mountain. The southern and western aspects are much the same, as I had been able to observe from Mount Erris to the SW the previous year.

Several of the higher cliff bands looked quite nasty, and as I glanced up from my lunch spot I seriously started to doubt if there was indeed a route through them. One massive band in particular simply looked impenetrable, although I couldn’t see some parts of it where it wrapped around short buttresses and gullies. Could there possibly be a scramble-friendly break somewhere? Well, only one way to find out!

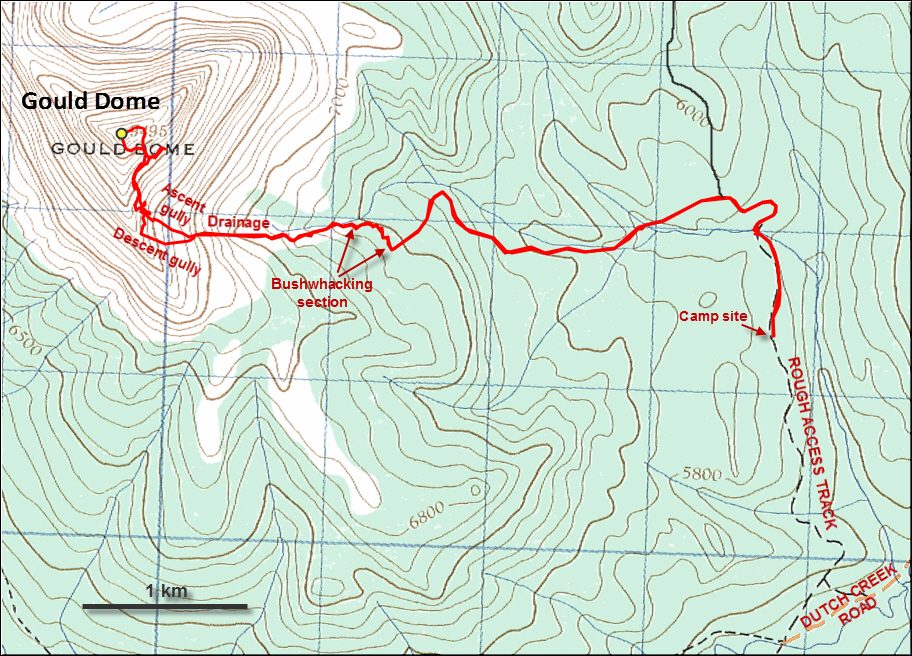

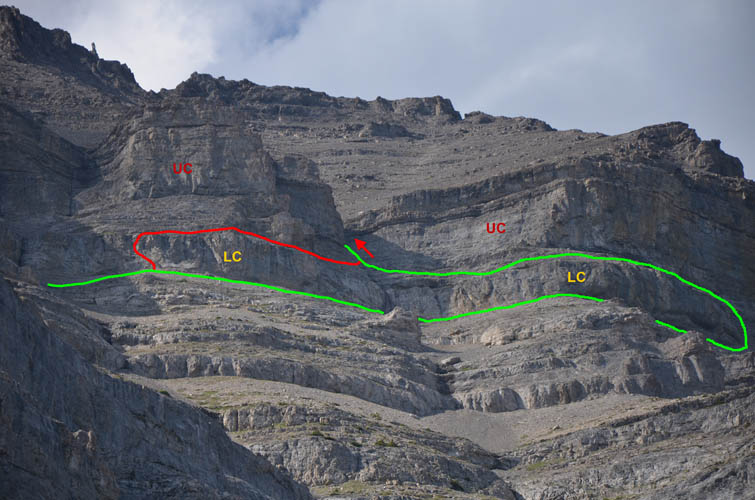

I continued up my drainage, which gradually turned into a rocky gully intersected by the many cliffs. There was some really enjoyable hands-on scrambling here and whenever the middle of the gully got too steep a bypass to the right or left would take me higher. This continued for quite a while, and the detours kept getting bigger and more complex. Eventually, my ascent came to a halt just underneath the huge, dark-coloured cliff and a second, vertical, light grey cliff directly below. There seemed to be a steep gully in the dark cliff band around a corner above to the right, but I just couldn’t see if it was going to work. First, I had to overcome the light grey band, which proved to be the main crux of the trip. It was only perhaps 4-5 m high and with solid holds, but quite steep. Once above that band, I veered right and could finally peek into the steep cleft that broke up the upper dark cliff band – a big sigh of relief… it was a go! Steep scrambling on water-worn rock requiring some stemming led me through and above this last obstacle.

The scree slope above the upper cliff band consists of terribly unstable rubble – so loose indeed that every step tends to dislodge a barrage of rocks bombarding whoever or whatever is below you. The gully through the upper cliff acts like a massive funnel, so needless to say that this break in the cliff is not a good place to linger around as rock fall (natural or hiker-induced) is a serious hazard here.

Loose scree covers almost the entire upper section of the mountain until you reach the narrow summit ridge, itself composed of fairly crumbly rock. A short scramble took me to the summit and its broken up cairn that looked like it had been hit by lightning. The Topographical Survey had made the first ascent in 1913, and Rick Collier’s party (with Bob Saunders, Reg Bonney and Carmie Callanan) had placed a register during their ascent in 1993. Only one other party’s visit is recorded in the register: Mark Sowinski, Mariann Azizi and Stephen Lowe apparently found the register wet and damaged and replaced it with a new one in 2003, which is still in great shape today!

The mountain’s name itself is quite an interesting story. The early explorer Thomas Blakiston, a naturalist from England, came through this area via the Livingstone Gap in the mid-1800s and was struck by the impressive dome-like shape of a tall massif he spotted to the west. He decided to name it Gould’s Dome after famous British ornithologist John Gould, whom he apparently revered. In 1915 the Boundary Commission, led by Morrison Bridgeland, renamed the highest peak of the massif “Tornado Mountain”, relegating “Gould’s Dome” or Gould Dome as it is known today to a lower and hitherto unnamed outlier to the south. Their survey crew had been caught in terrible storms on several occasions to reach the summit, so they must’ve felt that Tornado was a more fitting name. Whether Blakiston, or even John Gould, would’ve approved of this change is questionable, but despite the lower elevation Gould Dome is arguably no less intriguing to look at (and certainly more challenging to climb) than Tornado Mountain.

Gould Dome’s highest point affords spectacular views of a good portion of the High Rock Range, including the entire steep wall lining a number of peaks from Mount Domke and Mount Erris in the southwest to Funnel Peak to the west. Tornado Mountain sits directly to the north but it is obvious that a traverse from Gould Dome would be fraught with difficulties – a major climb over countless rotten ridges and cliffs, not something a scrambler like me would like to take on.

As much as I enjoyed the summit views, thoughts about the downclimb through those cliff bands were nagging in the back of my mind, so I decided not to while away too much time here and embark on the return journey instead. Tons of rocks of all sizes shot down the big scree pile and into the upper cliff gully as I started to descend, attesting to the fact that these slopes rarely see visitors, human or animal. Getting down the big cliff was surprisingly straightforward, and after some searching I even found a slightly easier way down the more difficult grey cliff band by contouring some 30-40 m to skier’s left (north), where an oblique weakness offered good holds to safely downclimb the wall. Past that, I followed my jagged uptrack through the lower cliff bands before eventually trending to skier’s right where there was some soft scree to speed up my descent down a side branch of my original ascent drainage.

All in all Gould Dome was a bit of a mixed bag. There is some good scrambling to be had in the long ascent gully, but tons of loose scree higher up make parts of the trip quite unpleasant. The steep walls and ledges are quite a challenge to negotiate. However, with sufficient patience, some serious route finding, and a willingness to detour, it seems the many cliff bands can be broken down into manageable scrambler-friendly steps.

DISCLAIMER: Use at your own risk for general guidance only! Do not follow this GPX track blindly but use your own judgement in assessing terrain and choosing the safest route. Please read the full disclaimer here.

Beautiful camp site with Gould Dome as my backdrop.

Approaching Gould Dome on an abandoned logging road.

Beyond the end of the logging road, and after a short bushwhacking section, a decent game trail leads through part of the forest.

This avalanche debris field needs to be crossed to get to the start of the drainage that snakes its way up the E slopes of the mountain (near centre of photo).

Lots of steps and cliffs present fun scrambling challenges higher up in the drainage.

Half way up I look over my shoulder to the south – Crowsnest Mountain in the distance.

Crowsnest Mountain (left) stands out like a sore thumb. To the right are Racehorse Mountain and a number of unnamed peaks.

Looking back up, the cliffs appear to get higher and now look more daunting… is there a way through?

To overcome the first serious rock band (the lower light grey band), a steep climb took me to the little green patch of grass, from where I could peek around the corner to the right to tackle the higher rock band. An easier (but still difficult) route through the lower band follows the base of the cliff and around the overhanging “bulge” on the far right side of the photo, where there is a weakness that’s unseen from here.

Looking back down from the green patch of grass.

Around the corner, a break through the upper cliff band opens up. It’s not overly difficult, but steep and the rock can be smooth.

View back down the break.

Once I’m through the cliff bands, it’s an easy yet tedious trudge up tons of rubble to the summit ridge.

Summit register.

Spectacular views of another “layer-cake” sub-peak to the north, with Tornado Mountain behind.

Close-up of Tornado Mountain. Definitely looks steep from here, but it’s not as bad as it seems.

Funnel Peak to the west.

A zoom reveals the double summit of Funnel Peak, with the high point to the west (left).

Mount Erris lies to the SW.

Rolling hills dominate the landscape between here and the Livingstone Range to the east. Thrift Peak (left) and Thunder Mountain (right) look like minor ridges from here!

I can’t get enough of the views around me!

The ridge that connects Gould Dome to the subpeak and Tornado Mountain to the north looks pretty nasty.

The descent through the two major cliff bands takes almost as long as going up! Thankfully, the weakness through the lower grey band seen here makes my life a little easier.

Some rare colour amongst all the grey rock.

There are numerous cliffs to zig-zag through. Arrow points at the “gateway” through the main cliff bands.

Gould Dome, east face: difficult route up the lower cliff (LC) in red, easier route in green. Both routes lead to a weakness that cuts through the upper cliff (UC).

Finally some stress-free hiking again along the familiar logging roads!

A young ptarmigan in the trees.