Continental Divide, AB, Canada

8 August 2019

Solo

A long approach for some beautiful scenery, horrible scree, and challenging climbing

Finally back in the Rockies again! After spending the summer travelling across Canada in our campervan and hardly seeing anything resembling a proper mountain (excepting perhaps Gros Morne or Mont Xalibu), I was more than ready to dive into my beloved Rocky Mountains again. It is perhaps this prolonged absence from the Rockies that made me pick an objective I knew wasn’t going to be the most pleasant… Andrew Nugara’s 2008 trip report of his ascent up Mount Farquhar was anything but encouraging: reading it made me think it might just be the worst trip he’s ever done, with tales of horribly loose talus, unstable rock, and tricky scrambling on the mountain’s summit ridge… But my threshold for such things had changed – perhaps disappeared – because I hadn’t seen them in so long, so I was prepared to take on the challenge.

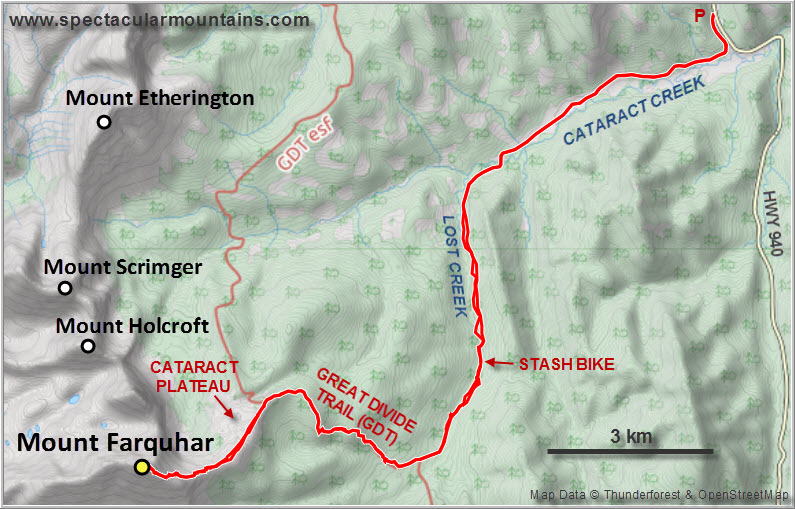

The day started with a terrible accident. I parked my van at the gate to the Lost Creek logging road (same trailhead as for Raspberry Ridge), packed up, got my bike ready, and started cycling down the dirt road. Only a few minutes in I hit a deep groove crossing the road on a downhill section. The weight of my pack (I brought almost four litres of water plus my big camera) combined with the fact that my crappy little mountain bike is way too small for me, resulted in my being catapulted forward, head first, and promptly thrown off my bike into the dust… I was so mad at myself for potentially having thwarted two beautiful days of hiking that I didn’t notice my bleeding left leg and aching ribs at first. I had fallen on my left side, with my pack taking the brunt of the impact but leaving a gaping wound on my left palm. There was no way this was going to be the end of my day, I thought, so I stubbornly patched up my hand and jumped back on my old bike which had been left unscathed. My ribs, on the other hand, turned out to be fractured when I came home a couple of days later.

Had it not been for this rather avoidable accident early on, the logging road approach would’ve been smooth sailing, which it was for the rest of the way. After about 8 km of biking along the Lost Creek logging road, I turned right on a smaller track down to the creek (#58 in Daffern’s K-country guidebook Vol. 5) and soon after stashed my bike in the bush as the going got a bit too rough for my liking. This is where the second roadblock of the day appeared: the track in front of me, a snowmobile route called “Oyster Trail”, soon disappeared in the creekbed, with no obvious bypass around the water. I probably wasted about an hour looking for the track and wading the creek three times before the washouts disappeared a couple kilometres further south. Fortunately, on the way back I managed to find a muddy trail on the west bank that avoided all the creek crossings.

The track then joined the Great Divide Trail (GDT), which steadily winds its way uphill through forest until emerging on a flat stretch of land called “Cataract Plateau”. This is a place of stunning natural beauty, one that makes you feel you’re on a different planet because it’s so remote yet so pleasant and charming. Vast green meadows with a few patches of trees stretch out into the distance where they gently roll uphill against the rugged grey limestone cliffs of Mount Farquhar along the Continental Divide. If only there was a source of water (I found none), this would be the perfect place to camp and play frisbee or soccer!

After sweating profusely on the long slog up the GDT to the plateau, I left the trail and took a nice long break on the meadows, soaking in the views of this pristine area. I felt really out of shape today, plus the bike accident had also taken its toll. And I really needed the rest – ahead of me was a mountainside full of loose, unstable chunks of angular rock, the most unpleasant kind of talus you can wish for anywhere. The NE ridge of Mount Farquhar features several steep cliffs, so sticking to solid rock along the ridge is not really an option. Instead, I had to sideslope to climber’s right (north) early on to avoid first a small cliff, then a more serious black rockband that extends northward quite a ways. Scree eventually buries this rockband, opening up a route to the top of the ridge, with many smaller cliffbands along the way. The terrain is steep and full of loose choss, and I felt excruciatingly slow during my slugging slog up.

While the scree slopes may only entail moderate scrambling, the continuation along the crest of the NE ridge is on a whole different level. A difficult climber’s scramble in my opinion, and all that with tons of exposure and lots of rubbly rock where even ropes might not help you for lack of stable anchor points. Crux after crux appeared, mostly in the form of steep cliffbands along the narrow ridge, and they just kept coming and coming. I was getting more and more mentally drained by the many challenges ahead of me, especially because I still couldn’t see where the true summit was. After what seemed like a long time, I finally got to the last hurdle, another steep narrow ridge section that I had to tackle “au cheval”-style. It was too narrow to walk across!

A pleasant surprise awaited at the summit cairn: a red Pelican case for a register, placed in August 2015 and containing a historical description of how the mountain was named along with a patch and crest of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

Mount Farquhar was officially named in 1919 after Lieutenant Colonel Francis Douglas Farquhar, who was born in England in 1875. Farquhar was instrumental in establishing the Canadian regiment called Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and was the unit’s first Commanding Officer. He fought in several wars, including the Boer War and in Somaliland. Farquhar was killed in action during WWI in 1915 in St. Eloi, Belgium.

Only one other entry was to be found in the booklet, an ascent dating back to August 2017. Nobody else seemed to have bothered climbing this peak since then, and to be honest I can see why. No doubt the views are stunning from the top as you sit atop the Continental Divide, your eyes sweeping over Alberta to the right and BC to the left, separated by a dramatic vertical wall just below you. Rarely visited peaks can be admired from here, including Mount Holcroft, Mount Scrimger and Gill Peak to the north, and Mount Pierce immediately to the south. However, despite the overwhelming beauty of the area and novelty factor of being in a seldom visited piece of the Rockies, the poor rock quality of Farquhar’s exposed NE ridge and terrible scree slog on the east slopes below are too miserable to overlook.

Owing to the many difficult downclimbs that required slow and careful moves, descending the mountain took me almost as long as ascending it. To make matters worse, I also ran out of water shortly after leaving the summit. The hot and sunny weather (31 degrees C in the valley!), plus the exhausting approach, had simply made me sweat too much. Without a ready water source nearby, I basically spent several hours without any water until I finally came by a small gurgling creek in the forest near the end of the GDT section of my route. What a refreshing treat to dip my sweaty head into the cool water!

The return back to my bike was swift and smooth, aided by a muddy trail along the west side of Lost Creek so I didn’t have to repeat the creek crossings again. I made it back to my van in the fading light by 9:30 PM, exhausted but happy to have conquered a remote mountain full of stubborn scree and tricky scrambling.

As a side note, Mount Farquhar’s east ridge was first scaled by John Martin in 1985 and rated PD+ / 5.4 to 5.6 according to the Rockies South Climber’s Guide by David P. Jones (2020). I personally would rate it on the lower end of that spectrum (perhaps up to 5.4), but I can see how one can easily argue that Mount Farquhar is not a scramble but a technical climb.

| Elevation: | 2894 m (my GPS) |

| Elevation gain: | 1510 m |

| Time: | 12.5 h |

| Distance: | 38.0 km (incl. 19 km of biking) |

| Difficulty level: | Difficult climber’s scramble (Kane), T6 / II (SAC) |

| Reference: | Nugara & own routefinding |

| Personal rating: | 2 (out of 5) |

NOTE: This GPX track is for personal use only. Commercial use/re-use or publication of this track on printed or digital media including but not limited to platforms, apps and websites such as AllTrails, Gaia, and OSM, requires written permission.

DISCLAIMER: Use at your own risk for general guidance only! Do not follow this GPX track blindly but use your own judgement in assessing terrain and choosing the safest route. Please read the full disclaimer here.