Central Highlands, Angola

13 January 2018

Solo

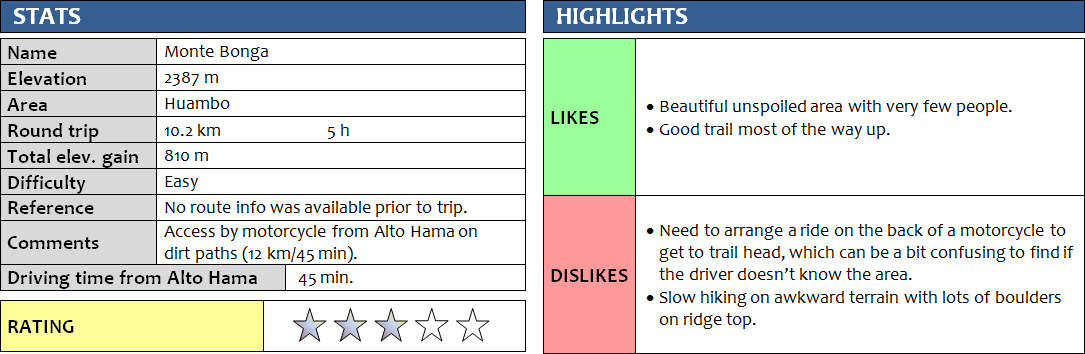

Monte Bonga is one of the mountains I had looked at on Google Earth before my trip to Angola. It’s clearly recognizable on elevation maps as one of the highest in the Huambo highlands, but as expected I couldn’t find any info whatsoever on how to hike it. My Bradt guidebook on Angola, the only English-language publication of its kind, doesn’t even have the word “hiking” in its index. The mountain is labelled “Mbonga” on some internet maps, but the locals I met in the area all call it Bonga (perhaps the M is silent?). Based on the satellite images I studied, it seemed possible to hike up along the east ridge starting on a dirt road below, with relatively easy access from the nearby town of Alto Hama. I had researched a few other interesting peaks in this area, including Angola’s highest mountain – Morro de Moco, so I decided to base myself in Alto Hama for a few days to explore the area after taking a long-distance bus down from Luanda, the capital of Angola.

Alto Hama turned out to be a nice little town with everything I needed: there was one hotel right at the main bus stop, a small grocery store right across where two friendly Mauritanian brothers were selling everything from toothpaste to soft drinks to bread, an open-air market with women selling fresh fruits and vegetables, two small restaurants, and a whole bunch of motorcycle drivers hanging around the main intersection in town and ready to take me anywhere I wanted to go. My hotel, the Pensão Hama, was simple but relatively clean. Since there was no electricity in town, a generator was used to provide power for 2-3 hours each evening, after that it was candles and headlamp. But at least I had a shower with running water and there was decent food to be found at the nearby Restaurante Ovimbundu, which as I later found out also doubles as a hotel. For 2000 kwanzas (ca. 4 euros), you can get a fairly tasty buffet dinner with things such as cow liver, potato stew, goat, boiled chicken, and funje (cassava flour cooked into a thick, viscous white porridge, an Angolan staple). Plus the ubiquitous Angolan Cuco beer that comes in yellow-red 350 ml cans and costs a whole 200 kwanzas (40 cents).

I had arrived late from Luanda last night – the bus ride that was supposed to take 9 hours had taken 16 hours, and I didn’t know anyone in town, so I hadn’t been able to talk to anyone or gather any info about hiking the surrounding mountains yet. During breakfast at the Ovimbundu restaurant, I started talking to some locals about my plans, which turned out to be quite tricky since the concept of hiking or going up mountains simply for pleasure is completely foreign to most Angolans, and quite understandably so. Moreover, nobody spoke English here and my Portuguese was pretty much non-existent. Somehow, however, I was able to make myself understood using my mediocre Spanish skills, since many words sound similar or are even the same in Portuguese. With the help of one of the guests in the restaurant, I managed to find Constantin, a kupapata (motorcycle) driver who was willing to take me around on his Indian-made Apache bike for the next few days in exchange for a reasonable payment. Of slim build, soft-spoken and of a more serious and reserved attitude, I took an instant liking to my new friend. And although he didn’t speak a word of English, he was quick to understand what I wanted and we somehow managed to communicate.

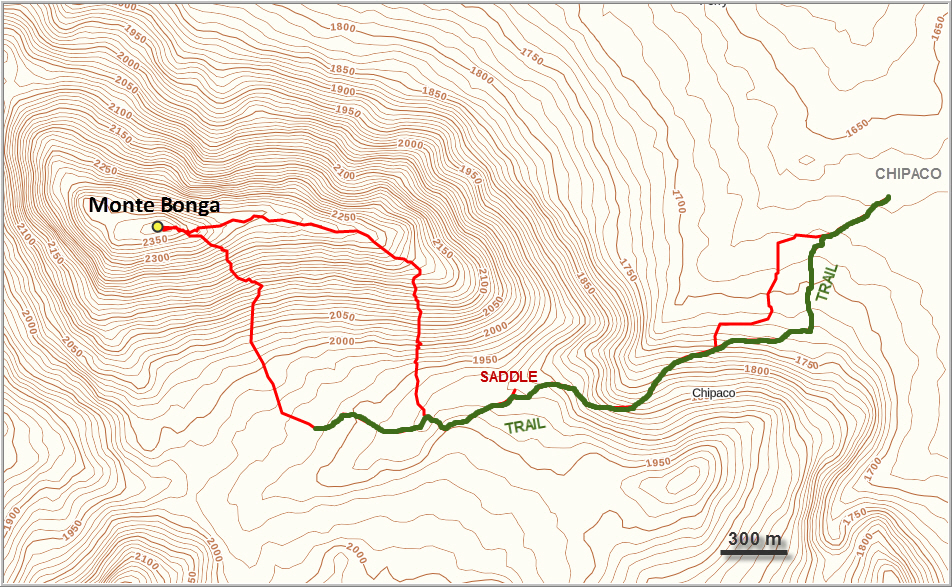

Half an hour after breakfast we picked up my hiking gear at the hotel and popped by the Mauritanian store for supplies. Bread, cookies, some soft drinks, and lots of water, plus the granola bars I had brought from home. Then we were on our way, me bouncing around on this backseat for the next 45 minutes on narrow dirt tracks through tropical bushland, fields and tiny villages. Every time we passed by a group of children they would inevitably stop whatever they were doing and just stare at me with wide-open mouths, but a quick wave and a smile seemed to unfreeze them and would always be returned with happy, smiling faces and lots of heartfelt laughter! We passed by men working their fields and women balancing baskets of fresh mangos on their heads, perhaps on their way to the local market, always returning our greeting with a friendly “bom dia”. There were no cars here, very few brick houses, and certainly no tourists. The “road” I thought I had seen on Google Earth turned out to be just a mud track, impassable for any motorized vehicles but bikes. We took a rather circuitous route with some shortcuts as the more direct “main road” had a broken bridge which even motorbikes avoid now. After passing through Bembua and Correia, we came to the small village of Chipaco where Constantin parked his motorcycle at a villager’s house to keep it safe for the day.

We had no idea where to start up the mountain. Constantin knows all the villages in the area, but has never been up any of the hills here and barely remembered the name of what I wanted to climb – Bonga, he simply exclaimed with a bit of bewilderment. I guess he still didn’t understand why I wanted to go up here. Quite frankly, I don’t blame him, as I sometimes don’t understand it myself! All we had to go by was the tentative route I had drawn in Google Earth that we now looked at on my iPhone in Gaia. The only problem was, the terrain all of a sudden didn’t look so inviting anymore… The valley I had intended to go up was blocked by a steep waterfall half way up, and the slopes to the sides were all covered with more trees than what the satellite images showed…somehow it was much more lush and vegetated that I had expected. But it was the rainy season after all, no wonder everything looked greener and denser. There was no way I wanted to bushwhack through this, it would’ve taken forever and certainly wouldn’t be fun!

About five minutes after setting out, we ran into a lone farmer with his ox. Not only was he able to confirm the name Bonga, but lucky for us he also showed us the starting point of a small trail that he said would take us almost all the way up. We walked through small maize fields and then entered a sparsely treed forest where the trail split into several smaller branches. A man chopping wood in the forest helped us find the main path again, which was now easy to follow. It took us along the side of the valley up to a small saddle. We were now the only people on the trail and it was beautiful to take in the forest with all its intriguing sounds of various chirping birds and humming insects all by ourselves.

Constantin was not a guide of course, he was my motorcycle taxi driver. Compared to me, he seemed woefully underprepared for our hiking endeavor. Lacking a backpack, I had to carry all our supplies, but I didn’t mind as I was glad to have a local with me to talk to anyone we ran into. Many people in the countryside speak only very basic Portuguese, if at all, and communicating with them would’ve been almost impossible for me. Constantin also turned out to be very pleasant company, an easygoing kind of guy who seemed trustworthy and reliable. He’s also quite fit and sure-footed and an excellent hiking companion. I felt sorry for him at first when I saw him hiking in a sweater, jeans and regular street shoes (without socks!), but then I realized that he had no problems whatsoever and was in fact quite comfortable in his clothes. After a couple of hours I was sweating profusely and my shirt was completely soaked, while Constantin was still wearing his sweater, hardly a drop on his forehead. Ah, the tropics!

At the saddle we poked around a bit to see if there was a way north straight up the ridge, but instead the trail took us west and down the other side into a small grassy high plain flanked by Bonga to the north and another smaller ridge to the south. It is here that we encountered the only other person during our trip, a lonely farmer guarding a small herd of cows. Just like the other people we had met, he was very friendly and eager to talk. “Are you searching for water?” he asked. Not sure if I had understood correctly, I looked at Constantin, who explained that “agua” in Portuguese means water of course but is also colloquially used to refer to mercury. The area around Huambo is known for its rich mineral resources, including gold, diamonds and quicksilver, which is apparently mined by some locals in small-scale, low-tech operations by hand. Foreigners are often involved in the local mineral trade, usually acting as middlemen buying the raw material cheaply from local chiefs and villagers, then selling it to merchants in Luanda or even exporting (or smuggling) them out of the country. My assertion that I was just a tourist wandering around the mountains was outright ignored by the farmer, who repeated his question what I was prospecting for. I smiled and Constantin uttered a few more polite words, then we said good-bye and quickly moved on.

In the middle of the grassy valley we decided to leave the path and head directly up the south slopes of Bonga. The terrain was steep and the many boulders and deep grass patches made for slow, strenuous hiking in the midday heat. The rock here is made up of various types of granite. To my disappointment, I found no evidence of either gold or diamonds… But then again I came here for other reasons, didn’t I?! For the scenery, for a nature experience, for an opportunity to explore the unknown – treasures that cost less than gold and diamonds and are easier to find.

Finally at the top of the main ridge, we continued slowly making our way to the summit towards the west. There was no sign of a trail here. No garbage, no cairns, no signs of human activity at all, just unspoilt nature. Shrubs, low-lying trees, long grass, and plenty of boulders. Certainly not the nicest terrain to walk on, but not difficult either. It was another 1.5 km of slow and cumbersome hiking to get to the summit of Bonga, with a couple of small dips along the ridge. A few scattered orange bricks at the highpoint are all that remains of a cairn that someone must’ve built a long time ago.

There are some great views of the many neighboring hills and peaks, none of which ever seem to see any hikers, a fantastic playground for further explorations, probably holding many hidden trails. Even distant Monte Luvili was poking through the clouds to the north, my objective for the next day.

Despite the dark clouds we had encountered in the morning, we were lucky it hadn’t rained all day. It was early afternoon by now and lots of clouds were slowly moving in from the east once again, so we didn’t want to push our luck and started heading back, this time using a more direct route off the main ridge back down the valley. I had a close call during a momentary lapse in concentration when I tumbled down 2 or 3 metres, almost hitting my head on a big boulder of rock – a stern reminder to take it slow and easy when descending.

After rejoining the trail in the grassy valley, we simply followed the trail back down the same way we came. We arrived back at the village around 3 pm after a fabulous adventure and my first taste of what Angolan hiking is like!

Notes on costs, logistics and security:

- Alto Hama, Hotel Pensão Hama: 5000 kwanzas (11 euros).

- Daily buses go from Luanda to Alto Hama: ca. 10-16 hours, 6300 kwanzas (13 euros). Huambo to Alto Hama takes 1 hour and costs 1000 kwanzas (2 euros).

- Cost of motorcycle ride from Alto Hama to village of Chipaco and back: 8000 kwanzas (18 euros).

- There are reportedly no landmines in this area, but always double-check before going out hiking in Angola.

- As in any African city, petty crime exists, but people are generally very friendly and welcoming. I always felt safe and never had any problems.

DISCLAIMER: Use at your own risk for general guidance only! Do not follow this GPX track blindly but use your own judgement in assessing terrain and choosing the safest route.

The adventure begins. Constantin with his Apache motorcycle takes me on dirt paths across the countryside.

It’s cloudy in the morning and looks like it’s going to rain…

In a light drizzle we start hiking towards Monte Bonga. We soon find a trail that takes us up the left side of the valley and towards the saddle seen here.

A friendly local chopping wood in the forest.

Funky looking mushrooms.

Time to take a break: soft drinks and cake, not exactly a healthy choice but easily available in town.

The trail through the forest is not very well-frequented.

A first look at the high valley and the south slopes of Bonga.

Beautiful long grass covers the upper valley.

The terrain on the slope of the mountain isn’t so pleasant. Lots of rock chunks and shrubs here.

View back down to the grassy valley, with several other hills in the distance to the south.

Close-up of Chipaco, the small village where we left the bike.

Looking west along the summit ridge.

Due to regular rain showers during rainy season now, the area is pretty green and lush.

It’s looking cloudy in the east. Thankfully, it didn’t rain anymore for the rest of the day.

The summit mass. Looks more difficult than it is, hardly any scrambling necessary.

Interesting vegetation here, perhaps akin to what one might find in Scotland or Ireland (minus the cacti)?

A few orange bricks, leftovers of a former summit cairn.

Cloudy vistas to the west.

To the north, the tip of craggy Monte Luvili pokes over a ridge in the distance.

Lots of other hills to explore here!

Constantin, my trusted companion at the summit.

Time to descend. It’s initially steep and quite bouldery, an easy place to trip.

Back down in the lovely high valley.

Walking back towards the village through maize fields.

A health centre in Correia on the way back to Alto Hama. Apart from some local churches, these were the only buildings made of brick in this area.

Last look back at Monte Bonga from the north.